simple

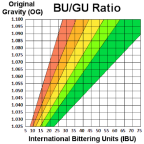

This week I take a look at some of the factors affecting how bitterness in beer is perceived and how they interact in a finished beer. Bitterness Perception in Beer For many years, I thought that the International Bitterness Units (IBU) level drove the overall bitterness level in a finished beer. As I matured as […]

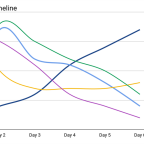

This week I take a look at some of the factors affecting how bitterness in beer is perceived and how they interact in a finished beer. Bitterness Perception in Beer For many years, I thought that the International Bitterness Units (IBU) level drove the overall bitterness level in a finished beer. As I matured as […]  This week I take a look at how yeast ferments wort into beer by looking at a simple graph from White Labs on the fermentation timeline. Fermentation Over Time Most of us know the basics of fermentation where yeast consumes simple sugars from the wort, chiefly maltose, and converts them into alcohol, carbon dioxide gas […]

This week I take a look at how yeast ferments wort into beer by looking at a simple graph from White Labs on the fermentation timeline. Fermentation Over Time Most of us know the basics of fermentation where yeast consumes simple sugars from the wort, chiefly maltose, and converts them into alcohol, carbon dioxide gas […]  This week I take a look at the best way to incorporate spices and flavor extracts into your beer brewing process. Examples of Spices, Herbs and Flavor Extracts Beer was not traditionally made with hops. In fact, the use of hops in beer dates back only about 500 years, while beer itself was introduced at […]

This week I take a look at the best way to incorporate spices and flavor extracts into your beer brewing process. Examples of Spices, Herbs and Flavor Extracts Beer was not traditionally made with hops. In fact, the use of hops in beer dates back only about 500 years, while beer itself was introduced at […]  I frequently get the question of how to transition BeerSmith data from one computer to another if you have purchased a new computer. This week I’m going to cover how to most easily transfer your local brewing data. It is important to note that BeerSmith desktop stores all of your “My Recipe” data locally on […]

I frequently get the question of how to transition BeerSmith data from one computer to another if you have purchased a new computer. This week I’m going to cover how to most easily transfer your local brewing data. It is important to note that BeerSmith desktop stores all of your “My Recipe” data locally on […]  John Palmer and Denny Conn join me this week to discuss simplified homebrewing and ways to save time and keep your beer brewing fun. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. Your browser does […]

John Palmer and Denny Conn join me this week to discuss simplified homebrewing and ways to save time and keep your beer brewing fun. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. Your browser does […] Awareness campaign comes after a number of significant keg theft incidents.

The post WA Brewers campaign targets keg theft appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

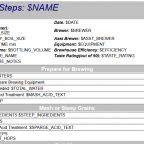

Some of the most frequent questions I receive on BeerSmith software are about how to properly set up and dial in your equipment profile. This is an important first step as the equipment you are using drives all of the critical recipe estimates like color, bitterness and original gravity. I’ve composed many articles and videos […]

Some of the most frequent questions I receive on BeerSmith software are about how to properly set up and dial in your equipment profile. This is an important first step as the equipment you are using drives all of the critical recipe estimates like color, bitterness and original gravity. I’ve composed many articles and videos […] What makes a good-looking brewery and taproom? Contributor Will McGough shows us a handful of his favorite remarkable brewery taprooms.

The post 9 Remarkable Brewery Taprooms appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Headed south to the Gulf Coast? Interstate 65 offers up several great craft beer cities to quench your thirst as you stop for the night.

The post The I-65 Craft Beer Route appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

This week I take a look at the differences between alpha and beta amylase which act during the mash to convert longer starch chains to simple sugars in beer. Alpha vs Beta Amylase Enzymes are naturally produced in malted barley during the malting process. Chief among these are alpha amylase and beta amylase. They are […]

This week I take a look at the differences between alpha and beta amylase which act during the mash to convert longer starch chains to simple sugars in beer. Alpha vs Beta Amylase Enzymes are naturally produced in malted barley during the malting process. Chief among these are alpha amylase and beta amylase. They are […] My parents didn’t drink much when I was growing up. Any alcohol that was in the house was hidden—hard stuff like vodka and tequila lived in a rarely opened cabinet in an armoire in the dining room, and what beer we had was stashed away in a second refrigerator in the garage. For years, the […]

The post One Style for All: The Complexity of Mexican Lagers and Latinx People in the Brewing Industry appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

This week I cover some of the basic concepts of using fruit in BeerSmith for making beer, wine, cider or meads. Fruit Basics BeerSmith 3 supports the use of fruit juice, purees, honey and whole fruits natively when making beer, mead, wine and cider recipes. Typically most fruits are added during primary or secondary fermentation. […]

This week I cover some of the basic concepts of using fruit in BeerSmith for making beer, wine, cider or meads. Fruit Basics BeerSmith 3 supports the use of fruit juice, purees, honey and whole fruits natively when making beer, mead, wine and cider recipes. Typically most fruits are added during primary or secondary fermentation. […] Learn how to brew better kettle sours then make your own at home with this all grain recipe.

The post All Grain Recipe: Zilwaukee Bridge Bruin appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

Stone & Wood’s 3.5% Green Coast Lager, a modern, easy-drinking lager made for the beer lover.

The post Made For Life’s Simple Moments appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

This week I take a look at how you can create custom reports in the BeerSmith desktop program. This feature is currently only available on the desktop version of BeerSmith. The process described below applies to BeerSmith 3. BeerSmith 2 had a slightly different setup where you need to copy your template to the Documents/Reports […]

This week I take a look at how you can create custom reports in the BeerSmith desktop program. This feature is currently only available on the desktop version of BeerSmith. The process described below applies to BeerSmith 3. BeerSmith 2 had a slightly different setup where you need to copy your template to the Documents/Reports […]  A tutorial on how to create a simple all grain beer recipe using BeerSmith Web. These same functions can be done on the desktop version or from your mobile device by logging into BeerSmithRecipes.com Related Videos: Recipe Design Tab | Recipe Adjustment Tools | BeerSmith Web Overview | Find/Scale Recipes | Pro Recipe Tips | […]

A tutorial on how to create a simple all grain beer recipe using BeerSmith Web. These same functions can be done on the desktop version or from your mobile device by logging into BeerSmithRecipes.com Related Videos: Recipe Design Tab | Recipe Adjustment Tools | BeerSmith Web Overview | Find/Scale Recipes | Pro Recipe Tips | […]  I’m pleased to announce the release of a web based version of BeerSmith 3 along with a desktop BeerSmith 3.2 update. The web based version allows you to edit your cloud based recipes from anywhere by simply logging into your cloud account at BeerSmithRecipes.com. BeerSmith Web Highlights Web based recipe editing from any browser by […]

I’m pleased to announce the release of a web based version of BeerSmith 3 along with a desktop BeerSmith 3.2 update. The web based version allows you to edit your cloud based recipes from anywhere by simply logging into your cloud account at BeerSmithRecipes.com. BeerSmith Web Highlights Web based recipe editing from any browser by […] American craft beers find their way into Japanese and Korean restaurants.

The post Spice, Fat, Acid, Beer appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

This week I wanted to share a more detailed look at the upcoming Web based version of BeerSmith which is scheduled for release in June of 2021. It will be available to all Gold+ license holders of BeerSmith 3. When released, you can simply log into your existing BeerSmithRecipes.com account and edit recipes in your […]

This week I wanted to share a more detailed look at the upcoming Web based version of BeerSmith which is scheduled for release in June of 2021. It will be available to all Gold+ license holders of BeerSmith 3. When released, you can simply log into your existing BeerSmithRecipes.com account and edit recipes in your […] Sydney Brewery’s Pilsner wins best in show at Queensland’s top beer awards.

The post The secret to the success of the quiet achievers appeared first on Beer & Brewer.

The holidays are an opportunity to combine your favorite beer styles with your favorite foods. Here is some simple holiday beer pairing advice.

The post Simple Holiday Beer and Food Pairings appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

The #1 winter seasonal beer1 returns with a crisper and brighter recipe and festive inspiration for holidays spent at home BOSTON, MA, Nov. 9, 2020—Samuel Adams brewers recognize the winter season will feel different this year, with many Americans taking “home for the holidays” literally. To spread some holiday cheer when drinkers need it most, […]

The post Samuel Adams’ New Winter Lager Brings A Wintery Remix To Holiday Classics appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

San Diego, CA (October 22, 2020) – PourMyBeer partners with Tappizza, San Diego’s latest pizza destination, to provide the ultimate pizza and beer experience with a 21-tap self-serve beer and hard seltzer beverage wall. Tappizza, located at 8242 Mira Mesa Blvd, is elevating the dining experience by putting its customers in control of their drinks, […]

The post San Diego Now Home to a Pizza and PourMyBeer Haven appeared first on CraftBeer.com.

Denny Conn and Drew Beechum join me this week to discuss hop techniques and brewing beers with unusual specialty ingredients. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. Your browser does not support the audio […]

Denny Conn and Drew Beechum join me this week to discuss hop techniques and brewing beers with unusual specialty ingredients. Subscribe on iTunes to Audio version or Video version or Spotify or Google Play Download the MP3 File– Right Click and Save As to download this mp3 file. Your browser does not support the audio […] It is tempting to say that beer isn’t like that. After all, each all-grain batch starts with the four basic ingredients and we do the rest… sure it would be a challenge to grow and malt barley, harvest and dry hops, isolate/propagate wild yeast, and haul water from a local stream, but what vessels would you use to boil/ferment? What about sanitizer, minerals, clarifiers, compressed CO2?

What follows is a high-level overview of what is required to brew a single batch of beer at Sapwood Cellars. Obviously, you could keep digging deeper into each one of these, peeling back layer-after-layer to the inputs of each input (e.g., the shoes that the hop harvester was wearing). I’ll arbitrarily stop where I lose interest. Needless to say though, the work of thousands in not millions of people goes into each of our batches. Scott and I just get the credit (or blame) because we're the ones at the end of the chain!

Ingredients

Water

Our water comes from Liberty Reservoir. From there it goes to Baltimore’s Ashburton water treatment plant. Baltibrew posted a nice series on the Baltimore water system. Luckily for us the existing minerals are mostly beneficial to the character of our beer. The carbonate is a bit higher than we’d like, but not by enough to require the waste of reverse osmosis.

Once pipes take it to the brewery it passes through a carbon filter to remove chlorine, and then an on-demand hot water heater. The fuel is natural gas piped into the brewery by BG&E (by way of fracking or older methods, and then refining). From there the water travels through a hose to our hot liquor tank where an electric element allows us to adjust the temperature. The electricity comes from a mix of fossil fuels, nuclear, and ~5% renewables.

To adjust the mineral content of the water, we add calcium chloride (from limestone-hydrochloric acid reaction or natural brine concentration) and calcium sulfate (harvested and refined from gypsum rock deposits). In addition, we add 75% phosphoric acid to adjust the pH of the water. Phosphoric acid is usually produced by combustion, hydration, and demisted from three ingredients: phosphorus, air, and water.

Grains

The grain we mash is a mixture of barley, wheat, oats, and rye depending on the beer. These are grown primarily on farms in North America and Europe. It is then soaked, sprouted, dried, and kilned by a maltster. The precise equipment required varies by malt and producer. In some cases it is a large industrial operation, in others the malt is still manually turned. The bulk of our base malt is Rahr brewer’s 2-row from Minnesota, but in our first order we also had sacks from Briess, Chateau, Simpsons, Crisp, Best etc. Most of the unmalted flaked grains (steamed and rolled to gelatinize their starches) are from Grain Millers.

We decided to hold-off on buying our own mill, to save the cost at the start… but after a few brews I can say a mill and auger are in our near future. We order our grains from Brewers Supply Group, which pre-mills the grain. We also occasionally add a few sacks to a Maryland Homebrew order from Country Malt.

Once we’re done with the now “spent” grain, they are picked-up by Keith of Porch View Farms. He feeds it to his animals as most of the carbohydrates are extracted into the wort, but proteins remain.

Hops

Our hops are grown throughout the higher latitudes of the globe, primarily the Pacific Northwest of the United States, but also Australia, Germany, and Czech Republic. The hops are first stripped from their bines, dried in an oast, and then baled. After selection, various lots are blended to create a consistent product and the hops are pulverized and pelletized. They are then vacuum-packed in mylar and stored cold to preserve their aromatics. Our hops primarily came from Hop Havoc, but we’re working on getting contracts for the upcoming harvest.

Yeast

Most of the yeast we’re using are the decedents of yeast that have been fermenting beer for hundreds or thousands of years. A couple hundred years ago their ancestors were part of a mixed-culture at breweries in England and Belgium, only to be lucky (and talented) enough to be isolated as a pure culture that gained success. Our Saccharomyces cerevisiae so far has come from RVA, Fermentis, and Lallemand for our “clean” beers. These needed to be isolated, propagated, and in some cases dried.

The sour and wild beers are too complex to track. They come from labs, bottle dregs, and a house culture. They may have come via a barrel, the breeze, an insect, or any number of other vectors into a brewery or labs. For example the Hanseniaspora vineae we are fermenting a hoppy sour for Denizen's Make It Funky festival came from Wild Pitch Yeast which isolated it from tree bark.

Fruit

We don’t have any beers far enough along for fruit, but we’re planning to source as much of it as we can directly from local farms and orchards. Most fruit is at its best when it is picked ripe and used quickly. I'm sure we'll use dried fruit, aseptic purees, juices, and freeze-dried fruits depending on quality, availability, and desired results as well. The first batch will probably be a tart saison on grape pumace (the pressed skins) from a local natural winery.

Other Consumables

Gas

Carbon dioxide is usually produced as a byproduct of some other activity (e.g., hydrocarbon processing). Our CO2 is stored in a 750 lb tank in a liquid state. We use it to carbonate and serve beer. It isn't economical at our scale to recapture the CO2 released by fermentation. Our supplier is Robert’s Oxygen.

As the air on Earth is 70% nitrogen it is usually concentrated with the use of a nitrogen generator. These rely on a membrane that allows nitrogen through. We need nitrogen to help push the beer through the long-lines from our walk-in to the tasting room (pure CO2 would lead to over-carbonation at those pressures). As the second most abundant gas in the atmosphere, oxygen generation uses similar technologies. We pump .5L/minute into the wort as it exits the heat exchanger, the yeast quickly uses it to create sterols for healthy cell walls when they bud. We get these two gases in large cylinders that are swapped out.

Chemicals

We need cleaners like caustic (sodium hydroxide) to remove organic deposits, and a phosphoric-nitric acid blend to remove inorganic beer stone and passivate the stainless steel. For sanitation we use iodophor for fittings in buckets, and peracetic acid for the tanks. These are made in a variety of industrial processes that I’m totally unaware of. Our chemicals are provided by Zep/AFCO.

Clarifier

Whirlfloc G helps proteins clump together in the last 15 minutes of the boil to be left behind. It is derived from Irish moss (seaweed) that is dried and granulated. As a vegan brewery, no gelatin or isinglass for us.

Barrels

Oak barrels start as oak trees. They are processed into planks, and then purchased by a cooperage which dries (either in a kiln or naturally). They are then assembled into barrels with metal hops, toasted, and sealed. From there they go to vineyards and distilleries that age their products in them. Beer is best in barrels that have already lost much of their oak character, so we buy them from other producers. A small amount of the wine or spirit is still present in the wood, providing a moderate contribution to the first batch, diminishing with each additional batch.

Equipment

The stainless steal for the vast majority of our equipment comes from China. Our brewhouse was constructed by Forgeworks in Colorado. Our fermentors and bright tank from Apex and DME in China. Our keg washer from Colorado Brewing.

The cooling of the fermentors is accomplished by a glycol chiller from G&D Chillers in Oregon. The ethylene glycol itself comes from ethylene and oxygen. The chiller also assists chilling the wort with our two-stage Thermaline heat exchanger (primarily more stainless steel). The copper pipes that carry the glycol are insulated with Armaflex. The flow of the glycol to individual tanks is controlled by electronic temperature sensors and solenoid valves.

Other equipment includes hydrometer, refractometer, pH meter, hoses, gaskets, and all manner of other valves and fittings.

For the space itself there was already plenty of concrete, bricks and metal. We hired Kolb Electric and B&B Pipefitters to do the installation of the bulk of the wires, pipes, and connections.

There is also everything that goes into serving a beer once it is ready. Kegs (Corny kegs for the sours and infusions, sanke for the standard clean beers), stainless steel fittings, beer lines, glasses (including the printed logo and the glasswasher) etc.

What’s the Point?

I don’t really have one. To me it is just remarkable how much of the complexity of brewing a batch of beer is now hidden in the inputs. I know how to brew beer at my house or a brewery, but if you put me out in the woods even with all the ingredients, I couldn’t brew a batch. Thinking about what is required for each batch makes me appreciate how nice it is to live in a time when I can brew beer as simply as going online and ordering the equipment and ingredients I want. It also shows me how much I still have to learn about making beer.

At the same time, it means that beers everywhere are mostly separated by the choices the brewer makes rather than the availability of ingredients. The exchange of information accelerated by the Internet. I hope there continue to be regional variations, specialties, and preferences. Traveling isn't as exciting when everyone brews NEIPA and pastry stouts.

The extent of the influence of aged hops on sour beer is still a bit underestimated. While the generally stated goal is preventing rapid souring by Lactobacillus in a traditionally fermented lambic, what they add to the flavor and what particular characteristics of the hops best serve this isn't widely studied. There are a few studies that oxidation can boost certain fruity aromatics. Which has lead Scott to threaten to use old hops on the hot-side for a NEIPA... he promised to do a test batch before brewing a 10 bbl batch on the new Sapwood Cellars brewhouse.

I thought it would be fun to brew with aged Cascades from the bines in my backyard, especially because fresh they didn't have a huge aroma. They'd been sitting open in my basement since they were dried a few years before.

I don't have the space or effort to grow or malt grain, so I took the easy way out and brewed with wheat malt extract (a blend of 65% wheat malt 35% barley). I'd had good results from extract lambics previously, but this time in addition to maltodextrin I added wheat flour slurry to the boil. Mixing the flour with cold water prevents it from clumping when it touches the boiling wort. A turbid mash pulls starch from the unmalted wheat into the boil, which eventually feeds the various microbes in the late-stages of fermentation. The microbes must have enjoyed it as the resulting beers are completely clear.

Fruit was provided by our four berry trees/bushes. Sour cherry, blackberry, raspberry, and mulberry. To keep things easy I added roughly equal amount of each (other than the raspberries). I briefly froze most of the fruit, but I added the raspberries a small handful at a time as they ripen slower than the rest. I only had enough of each for one gallon of beer, as most of the rest of the fruit was spoken for. The leftover beer went onto local plums!

Video Review

Backyard Berries

Smell – Cherry and raspberry lead, not surprising as they are more distinct than the blackberry and mulberry. There is an underlining wine-iness that likely comes from the rest of the fruit. The base beer behind the fruit doesn't make itself known other than a subtle maltiness.

Appearance – Clear garnet on the first pour, a little haze when I emptied the bottle into the glass. Alright head retention thanks to the wheat.

Taste – Reminds of the nose with raspberry up front and cherry jam into the finish. Not as bright and fresh as it once was, but still reasonably fresh. The malt and hops don’t add a huge amount of character, but they support the fruit. The Wyeast lambic blend similarly stays mostly out of the way, adding edge complexity without trying to fight through the fruit.

Mouthfeel – Not a thick beer given the relatively low OG, and all of the simple sugars from the fruit. Solid carbonation, CBC-1 did a good job despite the acidity.

Drinkability & Notes – The combination of four berries works surprisingly well to my palate. They play together without becoming generic fruitiness. The base beer is unremarkable, but that’s fine in a beer where the fruit is the star.

Changes for Next Time – Would be nice to brew more than a gallon, but otherwise my only real changes would be to go all-grain.

Plum-Bus

The rest of the batch went onto a two varieties of local plums. I've brewed with plums before in a dubbel. I wasn't sure about plums in a pale beer, but after trying spectacular examples from Tilquin and Casey I was convinced!

Smell – Clear it isn’t a kettle-soured fruit-bomb, lots of lemon pith and mineral along with the moderate fruit contribution. Plums aren’t nearly as aromatic as the more common sour beer fruits, but they add a depth without covering up the base beer.

Appearance – Beer is more rusty-gold than purple. Clear despite the flour. Thin white head, but this bottle appears less carbonated than the last few I’ve opened.

Taste – Tangy plum skin, apricot, and lemon. Beautiful blend of fruit and beer. Wyeast Lambic Blend with dreg-augmentation again does a really nice job. Strong lactic acid without any vinegar or nail polish. Finish is moderate funk, hay, and overripe stone fruit.

Mouthfeel – Light, but not thin. Carbonation is too low, maybe the cap-job on this one wasn’t perfect.

Drinkability & Notes – Delicious. The plum could be a little juicier and fresher, but it works well. Sad I didn’t leave any of this half unfruited for comparison.

Changes for Next Time – I’d like to keep experimenting with other plum varieties in beer. Glad the pale base worked out well. Despite “plum” being a common descriptor for darker Belgians, actual plums don’t shine with all of that malt.

Recipe

Batch Size: 10.00 gal

SRM: 5.5

IBU: 5.3

OG: 1.046

FG: 1.006/1.006

ABV: 5.25%

Final pH: 3.45/3.45

Boil Time: 90 mins

Fermentables

----------------

92.3% - 9 lbs Breiss Bavarian Wheat DME

5.1% - .5 lbs Maltodextrin Powder

2.6% - .25 lbs King Arthur All Purpose Flour

Hops

-------

2.50 oz - Homegrown Cascade: Aged 3-4 Years (Whole, ~1.00% AA) @ 90 min

Yeast

-------

Wyeast Belgian Lambic Blend

or

Omega OYL-218 - All The Bretts

Omega OYL-057 - HotHead Ale

Notes

-------

Brewed 1/15/17

Hops were homegrown and aged open over several years.

Fermented and aged in 6 gallon BetterBottle without transfering. Added some various dregs over the course of fermentation.

7/21/17 Filled a 1 gallon jug with the Wyeast half onto 6 oz each homegrown sour cherries, blackberries, and mulberries (plus maybe an ounce of raspberries - maybe 4 oz total over a couple months). The remainder went onto 3 lbs of methly plums.

8/24/17 Added an additional 1.75 lbs of Castleton plums to the plum portion

12/14/17 Bottled the 2.75 gallons of the plum with 61 g of table sugar and rehydrated CBC-1. Bottled the .8 gallons of backyard fruit with 21 g of table sugar and CBC-1.

Most recent update, December 2019:

---

On Friday I posted a visualization of the connections between the ownership of American breweries, both craft and macro. I was inspired by this graphic of American food companies and leaned heavily on existing aggregations. The response was enthusiastic. Between Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit it was viewed ~150,000 times, plus being featured in a Paste Magazine article.

However, it's the Internet so of course there were complaints:

- You're missing (insert recently sold or Canadian brewery)!

- You're lumping in total ownership with partial!

- List the rest of the 124 AB InBev owned breweries!

- That brewery is closed now!

- That logo is for the 7 Bridges in Da Nang, not Jacksonville!

I spent far too many hours over the weekend correcting, tweaking, and expanding the graphic to address many of those issues. Thanks to those who created other sources I could use as source material (/u/Hraes' spreadsheet, Craft Beer Joe, Philip H Howard, and of course Wikipedia).

Any visualization is a balancing act of information and intelligibility. My first version was likely too simple to provide any deep understanding of the complex web of brewery ownership... while the updated version may be so complex that it is overwhelming (and that's still without 108 AB Inbev brands).

Feel free to let me know if I missed anything. I intentionally left-off private equity firms that own a piece of a single craft brewery (e.g., Bruery, Stone). I'm sure that there are other conglomerations outside the US that didn't come to mind. It's already starting to look like one of those crazy conspiracy diagrams, so I'm not sure how much more I could add.

With this many complex relationships it is difficult to be completely accurate while maintaining legibility... especially when it comes to unique situations and convoluted relationships. So here it is without distinguishing different levels of ownership.

If you're reading this after July, 2018 don't expect the graphic above to be up-to-date. Obviously no rights other than fair-use claimed on the brewery logos.

I didn't start working on this with the goal of changing what beers people drink. I don't refuse to buy beer from "sellout" breweries... but all-else equal, I'd rather my dollars didn't go to a company that uses its size to muscle small craft breweries off the store shelf or tap list (for example). It's the same reason I stopped shopping at Northern Brewer and Midwest. In that regard there is a big difference between breweries owned by AB InBev, and to a lesser extend Molson-Coors, compared to those owned by CANarchy and Duvel-Moortgat. Even with those though, I'd rather support a small brewery where the money goes back into the brewery, rather than a private equity firm or international conglomerate.

Independent craft beer isn't always delicious. Wide-scale distribution of delicate beers takes both skilled brewers and a level of packaging and distribution channels that many small breweries don't have funding for. That said, I'm not going to buy an insipid or uninspired beer simply because it has a low-level of DO (dissolved oxygen) and an absence of diacetyl and acetaldehyde. There are enough great beers available that I don't need to sacrifice on quality or consistency!

Here is an interesting piece on the Old Dominion-Fordham relationship with AB InBev. Jim Lutz, CEO: "In the years I’ve been here I’ve only met with the AB InBev people twice..." I was fond of Old Dominion before they were acquired in 2007. The first noticeable change was that the tasting room went from smoke-free to smoking permitted. Pretty quickly they closed the brewery in Ashburn, VA and moved production to Fordham's facility in Delaware. The old head brewer didn't follow (he, along with the equipment, became Lost Rhino). I may be out of the loop, but I remember Old Dominion producing a few interesting beers (like their Millennium barleywine aged in barrels... and even a version with Brett). Now all I see from them are pin-up girl logos and uninspired beers. Whether that is the result of AB InBev or the brewery itself doesn't change many of the reasons I don't buy their beers.

While the Brewers Association had to draw a line somewhere for what is craft, I don't find anything special about the 25% non-craft brewery ownership definition. What really matters is the relationship between the brewery and ownership. How much control of the beers is put into the hands of marketing or accounting? What sorts of incentives/investments are there for brewing innovation versus sales growth. Are resources primarily used to increase consistency/quality, or reduce costs? In the past BA has been all too happy to raise the barrels-per-year cap for Boston Beer, even though producing ~4,000,000 bbls/year as a publicly-traded company owned by a billionaire puts their trade-group needs much closer to a macro brewer than it does mine as a ~1,000 bbl/year start-up brewery.

We're at an interesting time in the growth of craft beer, hopefully the visualization helps illustrate that!